Table of contents

If you’ve been diagnosed with PCOS, you probably remember the day you received that news—a mix of relief and apprehension about the future. On that day, your gynaecologist likely suggested taking a contraceptive pill. Perhaps you followed their advice, or maybe you were sceptical and declined.

In this article, we’ll explore everything you need to know about the pill when you have PCOS.

How does the pill affect your cycle?

The pill is a form of contraception designed to prevent pregnancy. It typically needs to be taken daily for 21 days, followed by a 7-day break or a week of placebo pills. During these 7 days, you experience withdrawal bleeding, commonly referred to as “false periods,” because this bleeding is triggered by the drop in synthetic hormones rather than your natural menstrual cycle.

Most pills contain synthetic oestrogen and progesterone, hence the term “combined pill.” These synthetic hormones are present in doses 20 to 50 times higher than your body’s natural levels. This significant dosage induces what is known as chemical castration, preventing your ovaries from functioning and halting ovulation. Essentially, the synthetic hormones override your natural hormones to suppress your menstrual cycle.

Additionally, the pill affects your brain by disrupting communication with your ovaries. Normally, your brain and ovaries work together to regulate hormone secretion throughout your cycle.

The pill also alters your cervical mucus, making it either sparser or thicker, which blocks sperm from entering and thus prevents fertilisation. Furthermore, it thins your endometrium to stop a fertilised egg from implanting, which is why your periods are often lighter while on the pill.

Cycle on the pill:

Natural cycle:

Different types of pills

Since your teenage years, you’ve probably tried several types of pills to find the one that suits you best, guided by your gynaecologist—even if you didn’t fully understand the differences between them. Micro-dosed, combined, triphasic, 2nd or 3rd generation—it all sounds confusing, doesn’t it?

Let’s break it down so you can understand your options more clearly.

Oestrogen-progesterone or Progestogen-only?

There are two main families of pills:

-

Oestrogen-Progesterone Pills, also known as Combined Pills: These contain synthetic oestrogen and progesterone (referred to as progestogen). Because this pill combines two different molecules, it’s called a "combined pill."

-

Progestogen-Only Pills, also known as Mini Pills: These contain only a progestogen, meaning they consist of just one type of molecule.

Monophasic, biphasic, triphasic, or quadriphasic?

These classifications apply exclusively to oestrogen-progesterone pills, which contain two different molecules.

The difference between these types of pills lies in the hormone dosage of the tablets within a single pack.

-

Monophasic Pill: All the tablets in the pack contain the same dosage of synthetic hormones.

-

Biphasic, Triphasic, and Quadriphasic Pills: These contain varying dosages:

-

Biphasic: Two different dosages.

-

Triphasic: Three different dosages.

-

Quadriphasic: Four different dosages.

Here’s a tip: TIf all your tablets are the same colour, it’s a monophasic pill. If not, the colour differences indicate dosage changes.

But why offer pills with different dosages?

Biphasic and triphasic pills were developed in the 1980s to reduce side effects like spotting between periods. However, no studies have conclusively proven they are more effective in doing so (1)(2).

Pill generations

When you hear about “pill generations,” you might recall controversies surrounding 3rd and 4th generation pills. The generation of a pill refers to the type of progestogen it contains.

The generation of a pill is defined by the type of progestogen it contains. This classification applies ONLY to combined pills that mix synthetic oestrogen and progesterone. These are the most commonly prescribed by healthcare professionals, such as Microgynon, Rigevidon, Ovranette, Yasmin, Cilest, Mercilon, Marvelon, Ovral, Cerelle, Yaz, to name a few.

So, the generation refers not to the pill itself but to the generation of the progestogen used. Each generation of progestogen corresponds to a specific molecule.

| Generation | Progestogens | Example Pills |

|---|---|---|

| 1st | Norethisterone Acetate, Lynestrenol | Brevinor, Norimin |

| 2nd | Levonorgestrel | Levest, Microgynon, Rigevidon |

| 3rd | Desogestrel, Gestodene, Norgestimate | Marvelon, Mercilon, Lizinna |

| 4th | Chlormadinone, Nomegestrol, Dienogest, Drospirenone | Yasmin, Zoely, Lucette, Eloine |

What is the issue with third and fourth generation pills?

These newer pills contain progestogens that increase the risk of vascular events (such as blood clots). The European Medicines Agency (EMA) confirmed a higher risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) for 3rd- and 4th-generation pills compared to earlier ones (3).

Why the pill doesn't regulate PCOS

PCOS is a condition with numerous symptoms. While the pill may relieve certain symptoms, such as acne and hirsutism, it does not regulate or treat the root causes of your PCOS.

Taking the pill only gives the illusion of a return to normalcy by simulating regular cycles. You’ll have periods every month thanks to the break between pill packs, but not because your body is successfully ovulating. In reality, the pill masks your symptoms and may lead to significant frustration when you stop taking it and your symptoms come back!

Taking the pill to regulate PCOS seems counterintuitive because you’re being offered a hormonal treatment that prevents ovulation when your body already struggles to ovulate. Framed like this, it probably doesn’t make much sense to you either!

The pill may even exacerbate some of your symptoms, as many side effects resemble PCOS symptoms: acne, weight gain, high cholesterol, water retention, digestive issues, irritability, fatigue, hair loss, and so on.

You must also consider that the causes of PCOS are varied and differ significantly from one woman to another.Naturopath Lara Briden, for example, identifies four types of PCOS: insulin-resistant, inflammatory, post-pill, and adrenal.

As you can see, PCOS is complex, and the pill won’t be enough to improve your symptoms. If you choose to take the pill, we recommend doing so while simultaneously adjusting your lifestyle. Adapting your lifestyle to PCOS will help alleviate your symptoms and ease the transition when you eventually stop taking the pill.

These recommendations align with official guidelines, which state that treatments are solely symptomatic and that it’s important to adjust your lifestyle to improve your symptoms. (4)

For deeper understanding, explore some of our other blog articles:

What impact can the pill have on PCOS?

As you’ve gathered, the pill stops your ovulation by severing the connection between your ovaries and your brain. Over time, this disruption can delay the return of your ovulation and natural cycles once you stop taking the pill. However, this isn’t the biggest issue when it comes to PCOS and taking the pill. The real concern is not producing progesterone, the post-ovulatory hormone essential for maintaining your hormonal balance.

When you have PCOS and your menstrual cycles are irregular or anovulatory (without ovulation), you lack progesterone because this hormone is only produced after ovulation. This lack of progesterone sustains the hormonal imbalance, potentially worsening symptoms such as anxiety, depression, water retention, weight gain, and acne. In the long term, it can create an inflammatory state that exacerbates your PCOS.

This inflammatory state can also be triggered by synthetic hormones. The pill places a significant burden on your liver, where it must be processed multiple times to be broken down and absorbed. Synthetic oestrogens, in particular, found in combined pills, can disrupt your liver function and metabolism. They may increase your cholesterol levels, triglycerides, reduce glucose tolerance, and heighten insulin resistance—exactly what we aim to avoid with PCOS.

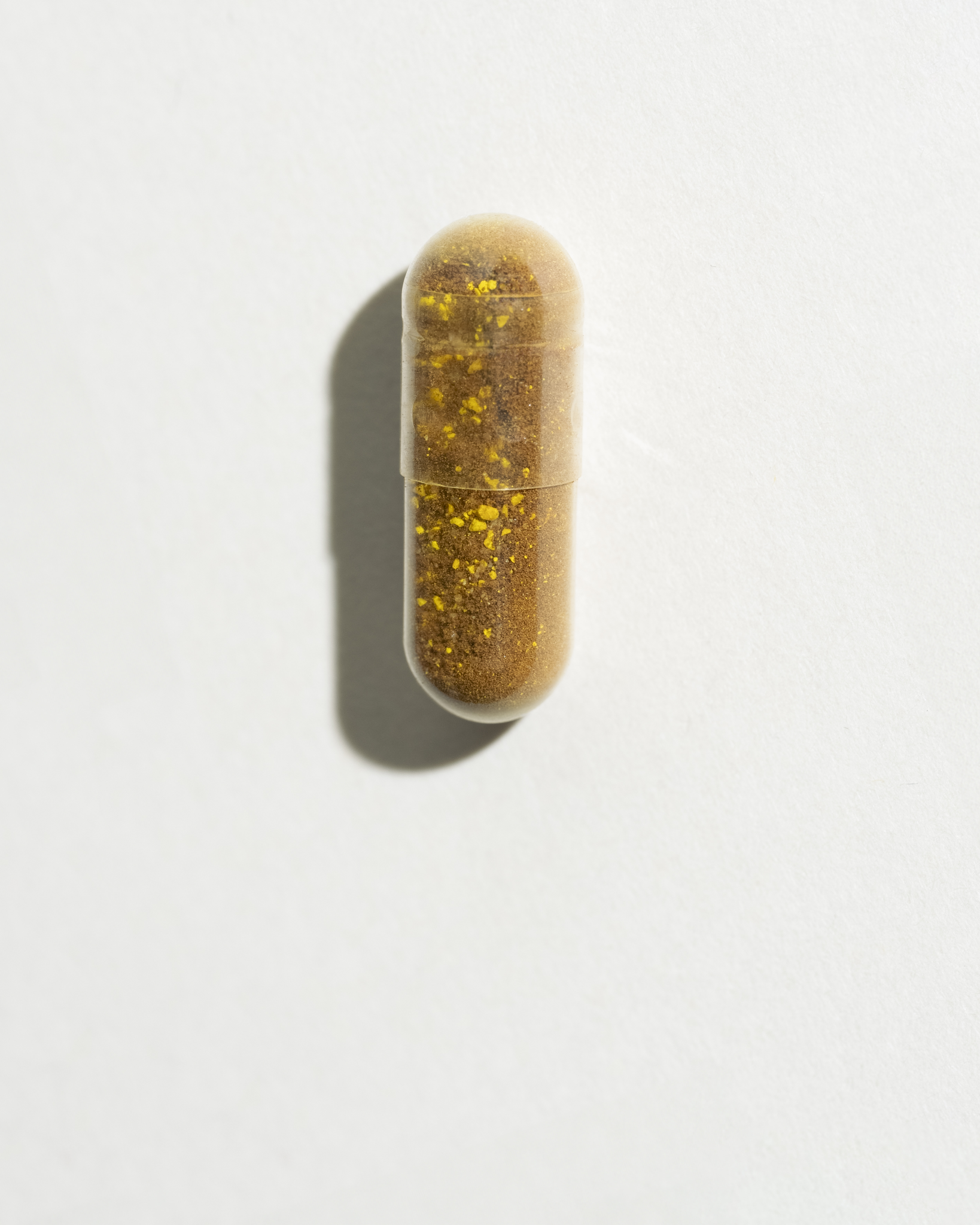

This additional strain on the liver depletes vitamins and minerals, leading to deficiencies within six months of starting the pill. Deficiencies in zinc, magnesium, selenium, iodine, and vitamins B6, B9, and B12 (not an exhaustive list) are common. These micronutrients are essential for a healthy menstrual cycle, ovulation being a key element for hormonal balance.

On the mental health front, recent scientific studies have shown that the pill can increase depression and anxiety in 20% of women (5), a group already more vulnerable to these conditions due to PCOS. The pill can also alter gut microbiota, which is crucial for both mental and digestive health.

In summary, taking the pill could delay the stabilisation of your PCOS, so we advise weighing the pros and cons before choosing the pill as a treatment. Consider the underlying causes of your PCOS and the factors that exacerbate your symptoms. For instance, if stress worsens your symptoms, it might be more beneficial to explore other options as a first approach.

If mental health is one of your concerns, check out our article: How PCOS Affects Your Mood and Energy.

Pros and cons of the pill according to your type of PCOS

There are four phenotypes of PCOS, which essentially determine the severity of your condition. These are classified from Phenotype A, which is the most severe, to Phenotype D, which is the least severe. (6) The consequences of stopping the pill will vary depending on your phenotype, meaning that the decision and approach to management will differ accordingly.

|

PHENOTYPE A |

PHENOTYPE B |

PHENOTYPE C |

PHENOTYPE D |

|

Hyperandrogenism |

Hyperandrogenism |

Hyperandrogenism |

X |

|

Polycystic Ovaries |

X |

Polycystic Ovaries |

Polycystic Ovaries |

|

Ovulatory Disorder or Anovulation |

Ovulatory Disorder or Anovulation |

X |

Ovulatory Disorder or Anovulation |

For example, women with Phenotypes A and B are at a higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular issues, and gaining weight easily. Conversely, women with Phenotype D are less prone to these metabolic disturbances.

For women experiencing complete amenorrhea (absence of periods) and not producing progesterone (Phenotypes A and B), it may be more beneficial to continue taking the pill to reduce the risk of endometrial and breast cancer. Indeed, if you do not ovulate for several months or even years, the imbalance between oestrogen and progesterone increases the risk of hormone-dependent cancers. (7)

On the other hand, for women with Phenotypes C and D, it may be easier and more advantageous to discontinue hormonal contraception, either because they ovulate (Phenotype C) or because their PCOS is not associated with hyperandrogenism (Phenotype D).

Which pill should you choose when you have PCOS?

PCOS is characterised by an excess of androgenic (male) hormones, leading to symptoms such as acne, hirsutism, and alopecia. Therefore, the most suitable pills for reducing these symptoms are those with low androgenic activity, those without androgenic effects, and anti-androgenic pills.

These categories of pills belong exclusively to the 3rd and 4th generations of contraceptives, which are associated with a higher risk of vascular problems. This is where making the best choice for your health becomes challenging.

As a tip, we recommend avoiding pills containing cyproterone acetate, found in Dianette, its generics, Cyprostat and Androcur. At high doses (≥ 25 mg/day), cyproterone acetate increases the risk of meningioma sevenfold after six months of treatment and twentyfold after five years of treatment. (8) By comparison, Dianette contains 2 mg of cyproterone acetate. (9) Although Dianette and its generics are low-dosed, it is advisable to delay their use and only employ them for short periods.

So, which pill should you choose for PCOS?

We recommend opting for a pill based on drospirenone, which has anti-androgenic effects and will help reduce symptoms such as acne, hirsutism, and androgenic alopecia. This type of progestogen also has a mild diuretic effect, which can help limit water retention and associated weight gain. (10)

Here is a (non-exhaustive) list of combined pills containing drospirenone: Dretine, Eloine, Lucette, Yacella, Yasmin, Yiznell.

You may also consider pills containing dienogest, norgestimate, or chlormadinone acetate. Dienogest, like drospirenone, has anti-androgenic effects and norgestimate reduces testosterone levels.

List of Pills by Progestogen Type

|

Progestogen Type |

Associated Pills |

Progestogen Action |

|

Dienogest |

Qlaira (11) |

Anti-androgenic action |

|

Norgestimate |

Cilique, Lizinna (12) |

Reduces testosterone levels |

Choosing the right pill: what they don't tell you

When choosing the right pill, you should not only consider visible symptoms or aesthetic concerns (acne, hirsutism, alopecia) but also also your medical history and lifestyle. These factors should be thoroughly evaluated by a healthcare professional.

Firstly, by ensuring you don’t have absolute contraindications to taking the pill, which include:

- Arterial or venous accident

- Cardiovascular disease

- Predisposition to thrombosis

- Migraines with aura

- Smoking (more than 10 cigarettes a day)

- Abnormal lipid profile (total cholesterol, HDL, LDL, triglycerides)

- History of breast or endometrial cancer

Secondly, by considering relative contraindications, which should prompt you to weigh the benefits and risks of taking the pill. These relative contraindications include:

- Smoking (fewer than 10 cigarettes a day)

- Diabetes

- Obesity

- Benign mastopathies (a sign of oestrogen excess)

This information will help guide you towards a specific type of pill. For example, if you’re a smoker with PCOS, you might want to consider progestogen-only pills with anti-androgenic effects, like Slynd. It’s preferable for smokers to choose progestogens over combined pills due to the cardiovascular risks.

If you have no contraindications, feel free to try different pills to find the one that suits you best—always under the guidance of a healthcare professional. To ensure your safety, you might also consider requesting an annual lipid profile check to confirm that your body is tolerating the pill well.

PCOS, the pill, and mental health

When you have PCOS, stopping the pill can completely disrupt your body and make your symptoms uncontrollable for several months. Learning to manage your symptoms also takes time and effort, which can feel like an additional mental burden. Moreover, it can represent a financial cost, making it inaccessible for some.

If you’re considering stopping the pill, we advise you to first take into account your mental health. Are you going through a difficult time? Is your environment supportive? Do you feel ready to take on new challenges? Do you have the strength to change your habits?

If the answer is no, and you need to prioritise your mental health, we recommend continuing the pill until you feel better. We also suggest seeking advice from a healthcare professional (gynaecologist, midwife, endocrinologist, psychiatrist, psychologist). Your GP, who knows you well, may also provide personalised advice suited to your personality and lifestyle.

You might also consider a compromise by combining the pill with supplements and lifestyle adjustments to better control your symptoms. (14)

We hope this article helps clarify things and aids you in making the best choices for your physical and mental health. Remember, the best contraception is the one you choose!

- Ovulation: The release of an egg from the ovary. The pill stops this process entirely, which is why bleeding on the pill is not a real menstrual period. = Ovulation: The release of an egg from the ovary. The pill stops this process entirely, which is why bleeding on the pill is not a real menstrual period.

- Withdrawal bleeding: Bleeding that happens during the pill-free week due to a drop in synthetic hormones. It mimics a period but does not mean you have ovulated. = Withdrawal bleeding: Bleeding that happens during the pill-free week due to a drop in synthetic hormones. It mimics a period but does not mean you have ovulated.

- Estrogen & progestin (synthetic hormones): Artificial versions of hormones used in the pill to prevent ovulation and control the cycle. They influence skin, mood, metabolism, and more. = Estrogen & progestin (synthetic hormones): Artificial versions of hormones used in the pill to prevent ovulation and control the cycle. They influence skin, mood, metabolism, and more.

- Androgens: “Male” hormones (like testosterone) that are often elevated in PCOS. High androgens cause acne, hair growth, hair loss and irregular cycles. = Androgens: “Male” hormones (like testosterone) that are often elevated in PCOS. High androgens cause acne, hair growth, hair loss and irregular cycles.

- Micronutrient depletion: Some forms of birth control may reduce levels of key nutrients like B vitamins, zinc and magnesium, which the body needs for hormonal balance and energy. = Micronutrient depletion: Some forms of birth control may reduce levels of key nutrients like B vitamins, zinc and magnesium, which the body needs for hormonal balance and energy.

Scientific references

SOVA was created by two sisters with PCOS who wanted products that truly worked. Our formulas are developed in-house with women’s health and micronutrition experts, using ingredients backed by clinical studies and compliant with European regulations.

- Built by women with PCOS, we know the reality of the symptoms.

- Clinically studied, high-quality ingredients, including patented forms like Quatrefolic® and an optimal Myo-/D-Chiro Inositol ratio.

- Holistic support for hormonal balance, metabolic health, inflammation, mood and cycle regulation.

- Transparent, science-led formulas with no unnecessary additives.